5 Ways We Can Keep Your Immune System Strong

December 10, 2025/by Kaplan Center

Want to Take Your Workout to the Next Level Next Year? These Tips Can Help

December 8, 2025/by Kaplan Center

Dr. Kaplan’s Dos and Don’ts of the Holiday Season

December 3, 2025/by Kaplan Center

Let’s Talk Webinar – A Root Cause Q&A

December 2, 2025/by Kaplan Center

Navigating Holiday Meals with Gut Issues: Simple Tips for a Comfortable Season

December 1, 2025/by Chardonée Donald, MS, CBHS, CHN, CNS, LDN

Craniosacral Therapy for TMJ | Say Goodbye to the Daily Grind

November 19, 2025/by Patricia Alomar, M.S., P.T.

From Compassionate Care to Personal Healing: A Letter to My Patients

November 18, 2025/by Kaplan Center

8 Steps to a Healthier Gut—and a Longer, Healthier Life

November 18, 2025/by Kaplan Center

Mid-Life Irritability & Fatigue Improved by Hormonal Balancing

November 13, 2025/by Lisa Lilienfield, MD

From Challenges to Change: Dr. Kaplan on Healthcare’s Biggest Challenges

October 29, 2025/by Kaplan Center

Overlooked Dangers of Mold Exposure and How to Stay Safe – Dr. Kaplan Talks to WUSA9

October 27, 2025/by Kaplan Center

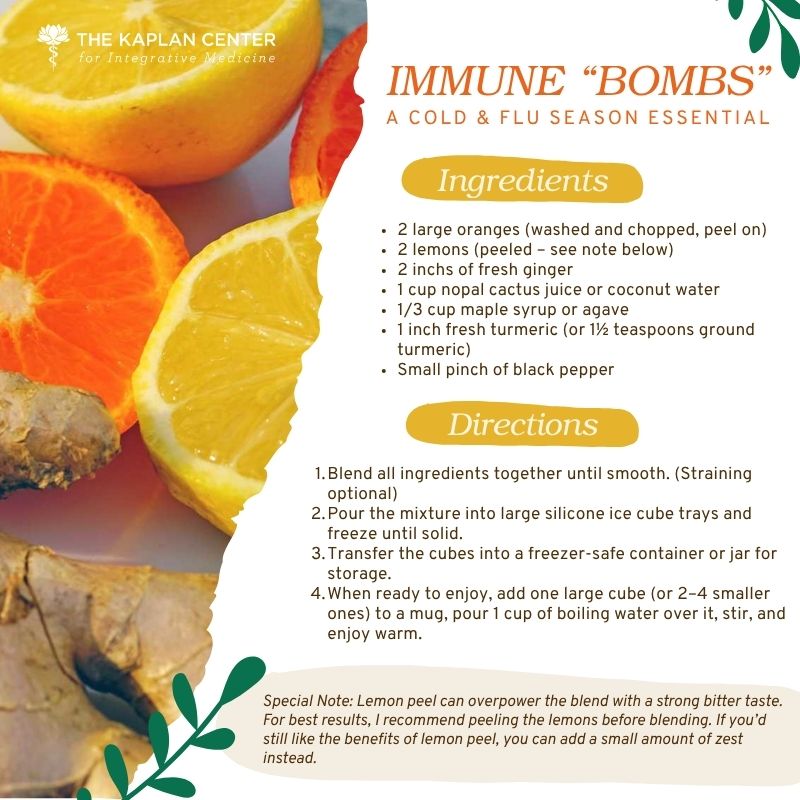

Let’s ‘Fall’ Into Wellness: A Nutritionist-Approved Immune-Boosting Recipe for Cold and Flu Season

October 13, 2025/by Chardonée Donald, MS, CBHS, CHN, CNS, LDN

PANS/PANDAS – When Sudden Symptoms Signal Something More

October 9, 2025/by Kaplan Center

Beating Burnout, A Nutritionist’s Perspective

October 1, 2025/by Chardonée Donald, MS, CBHS, CHN, CNS, LDN

3 Things That Can Happen After Stopping GLP-1s

September 11, 2025/by Chardonée Donald, MS, CBHS, CHN, CNS, LDN

What Families Need to Know About COVID and Flu Season

September 3, 2025/by Kaplan Center

September is Pain Awareness Month

September 1, 2025/by Kaplan Center

Dr. Kaplan Spoke to Northern Virginia Magazine About COVID, Flu, and Immunity — Here’s What You Should Know

August 14, 2025/by Kaplan Center

“Why Do I Feel Like Crap?”: The Overlap Between Long COVID and Perimenopause

July 30, 2025/by Kaplan Center

Why People Are Turning to EMDR (and Why You Might Want to Too)

July 23, 2025/by Kaplan CenterAre you looking to improve your overall wellness?

Personalized care you can trust.

Our integrative, non-surgical treatment approach is highly successful in maintaining wellness and also treating chronic pain and illness. For more than 30 years, we have delivered superior, cutting-edge health care in the Washington, DC area.

QuickLinks

Contact Information

Tel: 703-532-4892

Fax: 703-237-3105

6829 Elm Street, Suite 300

McLean, Virginia 22101

Map It

Hours of Operation

Mon – Thu : 8 am – 5 pm, ET

Fri : 8 am – 12 pm, ET

"What Gluten Does" An Excerpt from Total Recovery

/in Digestive Issues, Nutrition/by Gary Kaplan, DOThe following is the third in a series of excerpts on gut health from Dr. Gary Kaplan’s book “Total Recovery: A Revolutionary New Approach to Breaking the Cycle of Pain and Depression.”

“Leaky gut has been implicated in the growing number of food and environmental sensitivities affecting almost 25 percent of American adults. These are not food allergies, but delayed hypersensitivity reactions.1

As many as 40 percent of Americans are sensitive to gluten. One in 100 of those has a severe reaction in the form of an autoimmune disease, celiac disease.2

“Imagine gluten ingestion on a spectrum,” says Dr. Allesio Fasano, head of research at the University of Maryland Celiac Research Center. “At one end, you have people with celiac disease, who cannot tolerate one crumb of gluten in their diet. At the other end, you have the lucky people who can eat pizza, beer, pasta, and cookies – and have no ill effects whatsoever. In the middle, there is this murky area of gluten reactions, including gluten sensitivity or intolerance. This is where we are looking for answers.”3

Most doctors don’t know the difference. Some are unaware that gluten sensitivity can genuinely contribute to hundreds of diseases and that the symptoms may not manifest in the gut, but in other parts of the body.4

Years ago, we believed that celiac disease was a rare childhood syndrome. Today the average age of diagnosis is in individuals between ages 40 and 60. Celiac disease affects more than 2 million Americans – 1 in 133 people.5 Researchers have already confirmed that the dramatic rise in figures is not due to greater awareness. By testing old blood samples, they have shown that, in the last 50 years, the rate of celiac disease has increased fourfold.

Gluten intolerance is now estimated to affect 6 to 9 percent of the American population. Furthermore, people in their seventies, who have eaten gluten without problems their entire lives, are now experiencing gluten sensitivity.6

Unfortunately, gluten intolerance is sometimes viewed with skepticism. When the tests come back negative for celiac disease, many doctors dismiss their patients’ complaints rather than investigating further. Part of the problem is that, like allergy tests, gluten intolerance tests are not consistently reliable. While gluten intolerance is not an allergy to gluten, we have not yet found a definitive means of identifying it in the blood.

The only absolute way to determine gluten intolerance is to completely remove gluten from the diet for 6 weeks and see if the symptoms improve. It can be hard to tell. If there are other food intolerances and nutritional deficiencies at play, removing gluten may only eliminate some of the symptoms.

Peter Green, MD, director of the Celiac Disease Center, estimates that research into gluten intolerance is about 30 years behind celiac research.7 Without better research, patients are too often told it’s “all in their heads.” With a burgeoning series of product lines of gluten-free foods, estimated at $2.6 billion in sales last year alone, it is easy to assume that gluten intolerance is nothing more than a fad.8

It’s widely known that agricultural changes in wheat production over the past decades have altered wheat significantly and raised both its protein and gluten content.9 Some ascribe gluten sensitivity to the increase in our consumption of wheat. Gluten can now be found in everything from bread and canned goods to hand lotion and makeup.10 But the evidence is inconsistent. And the cause may lie in the bacteria in the gut itself. We’re beginning to suspect that gut bacteria determine whether the immune system treats gluten as food or as a deadly invader.11

In his studies of celiac disease, Dr. Fasano made an important discovery. He studied 47 newborns who were genetically at-risk for developing celiac disease. By the time they were 2 years old, these children had a fairly impoverished and unstable community of intestinal bacteria.12 As he continued to monitor their bacterial levels, the levels of lactobacilli declined in two children.

Both developed autoimmune diseases. One got celiac disease, and the other type 1 diabetes (which has a genetic proclivity similar to that of celiac disease).13

Dr. Fasano and his colleagues were excited. “Imagine what would be the unbelievable consequences of this finding,” he said. “Keep the lactobacilli high enough in the guts of these kids, and you prevent autoimmunity.”14

The questions is, was it the chicken or the egg? Which came first, the imbalance of bacteria or the autoimmune disease? Some studies show that intestinal inflammation accommodates bacteria that keep the inflammation going.15 As we’ve already observed, bacteria learn and fight hard to survive.

It’s a living system, where different choices can be made at any stage. Our genetics help determine our bacteria, but the bacteria can change us – turning genes off and on, adapting as they go. According to Bana Jabri, director of research at the University of Chicago Celiac Disease Center, even if the chicken comes first, the egg can contribute. “You have the same endpoint,” she says, “but how you get there may be variable.” Such complexity both confounds notions of one-way causality and suggests different paths to the same disease.16″

1 Lipski, Digestive Wellness

2 A. Fasano, “Zonulin and Its Regulation of Intestinal Barrier Function: The Biological Door to Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Cancer,” Physiological Review 91, no. 1 (January 2011): 151–75, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21248165.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 A. Fasano et al., “Prevalence of Celiac Disease in At-Risk and Not-At-Risk Groups in the United States,” Archives of Internal Medicine 163, no. 3 (February 20, 2003): 286–92, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12578508.

6 Melinda Beck, “Clues to Gluten Sensitivity,” Wall Street Journal, March 15, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748704893604576200393522456636.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Moises Velasquez-Manoff, “Who Has the Guts for Gluten?” New York Times, February 23, 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/02/24/opinion/sunday/what-really-causesceliac-disease.html.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

Reprinted from Total Recovery: A Revolutionary New Approach to Breaking the Cycle of Pain and Depression by Gary Kaplan, D.O., with permission from Rodale Books. Copyright (c) 2014 by Gary Kaplan, D.O..

To read Part 1 of this series, “Gut Feelings,” click here.

To read Part 2 of this series, “Hidden Immune System,” click here.

“Hidden Immune System”: An Excerpt From Total Recovery

/in Digestive Issues, Wellness/by Gary Kaplan, DOThe following is the second in a series of excerpts on gut health from Dr. Gary Kaplan’s book “Total Recovery: A Revolutionary New Approach to Breaking the Cycle of Pain and Depression.”

“When scientists realized that 70 percent of our immune system was located in and around our digestive systems, it was a staggering discovery. Unlikely as it seems, one of the primary reasons for this is bugs. We are only just beginning to comprehend how much we rely on these colonies of microscopic bacteria. Our health is dependent on the trillions of bacteria in our guts.

Ever since 1674, when Dutch scientist Anton van Leeuwenhoek first observed bacteria with a single-lens microscope, some of our biggest medical breakthroughs have involved getting rid of bacteria. The process of pasteurization, discovered by Louis Pasteur, was based on killing bacteria by heating milk to make it safer to consume. In 1905, Robert Koch won the Nobel Prize for proving that bacteria can cause disease, reinforcing the idea that bacteria are best avoided.

It has long been suspected that the bubonic plague (the Black Death), which wiped out an estimated one-third of Europe’s population from the 14th to 18th centuries, was caused by an infectious bacteria. Only as recently as November 2012 did anthropologists finally confirm that this devastating disease had indeed been caused by bacteria, after carefully examining the DNA of skeletons buried in “plague pits” throughout France, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Although they hadn’t known how the plague was being passed from person to person, physicians like Nostradamus, who recommended hand washing and clean linens (free from plague bacteria), earned their reputations by reducing the spread of the disease.

It’s stories like this that have led us to, rightly, associate bacteria with disease. By the 21st century, we’ve established a trend for keeping our environments as clean as possible, improving sanitation, dispensing vaccinations, taking antibiotics at the least sign of infection, and supporting a thriving industry in antibacterial soaps and cleaners.

Our enthusiasm for cleanliness may have taken us too far. We didn’t understand the nature of bacterial flora in our intestines and how vital they were to our health. The contemporary “hygiene hypothesis” suggests that it is the continual exposure to bacteria in early childhood that helps us build strong immune systems. When children are protected from contaminants, they are actually at greater risk for asthma, allergies, food sensitivities, and immune disorders.”

1 Lipski, Digestive Wellness

2 Carlo M. Cipolla, “A Plague Doctor,” in The Medieval City, edited by Harry A. Miskimin, David Herlihy, and A. L. Udovitch (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977).

3 Lipski, Digestive Wellness

Reprinted from Total Recovery: A Revolutionary New Approach to Breaking the Cycle of Pain and Depression by Gary Kaplan, D.O., with permission from Rodale Books. Copyright (c) 2014 by Gary Kaplan, D.O..

To read Part 1 of this series, “Gut Feelings,” click here.

To read Part 3 of this series, “What Gluten Does,” click here.

“Gut Feelings”: An Excerpt From Total Recovery

/in Inflammation/by Gary Kaplan, DOThe following is the first in a series of excerpts on gut health from Dr. Gary Kaplan’s book “Total Recovery: A Revolutionary New Approach to Breaking the Cycle of Pain and Depression.”

“We now know that our intestinal tract has 100 million nerves – more than our spinal cords or peripheral nervous systems. With this radically new understanding, scientists have tentatively begun to refer to it as the body’s second brain.

As Michael Gershon, MD, explains in his book The Second Brain, the intestinal tract is far more independent than anyone had realized. It is even equipped with its own senses and reflexes.1

Surprisingly enough, our digestive systems manufacture just as many neurotransmitters as our brains. With the advent of “designer drugs” – such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) – we have come to think of depression, anxiety, and insomnia in relation to the amount of serotonin circulating in the brain. Only recently has it become apparent that 95 percent of the body’s serotonin is manufactured not in the brain, but in the gut.2

Now it makes sense that the side effects of SSRIs often include intestinal problems.

In America more than two million people have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which may be caused, in part, from too much serotonin in the intestinal tract. As Adam Hadhazy points out in Scientific American, this means IBS – like other diseases caused by an imbalance of neurotransmitters in the gut – could almost be considered “mental illnesses” of the second brain.3

IBS may also signal an inflammatory process in the spinal cord or brain itself. An emergent theory on the cause of IBS is that it is a form of central sensitization. Inflammation in the spine increases sensitivity of the nerves controlling the muscles that line the intestinal tract and ensure the smooth flow of food throughout our digestive system. When the nerve signals from the spinal cord and brain to the intestines are disrupted, it can cause the intestinal muscles to spasm, resulting in pain and cramping. The muscles respond by becoming overactive (diarrhea) or underactive (constipation).4

As researchers have turned their attention to serotonin levels in the gut instead of in the brain, it has led to even more surprises. In a study of rodents at Columbia University Medical Center, scientists found that when they gave rodents with osteoporosis a drug that inhibited the release of serotonin in the gut, the disease disappeared. Gerard Karsenty, MD, lead author of the study and chair of the Department of Genetics and Development at Columbia, admitted, “It was totally unexpected that the gut would regulate bone mass to the extent that one could use this regulation to cure – at least in rodents – osteoporosis.”5

Dr. Gershon says, “We have never systematically looked at [the intestinal tract] in relating lesions in it to diseases like we have for the [central nervous system].”6 Once we have had time to investigate the implications of the second brain, important connections to diseases will be linked to the state of our gut.

We know that problems in the intestinal tract can go much further than heartburn and indigestion or constipation. Crohn’s disease, IBS, and ulcerative colitis also arise from imbalances in the gut.7 Early studies have suggested that imbalances in intestinal bacteria can cause “arthritis, diarrhea, autoimmune illness, B12 deficiency, chronic fatigue syndrome, cystic acne, colon and breast cancer, eczema, food allergy or sensitivity, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, psoriasis, and steatorrhea.” None of these conditions were previously recognized as being related to gut bacteria.8

Gradually, physicians reading the latest research are becoming aware that migraines are frequently triggered by food sensitivities that inflame the gut.9

Diseases like chronic fatigue syndrome, asthma, and fibromyalgia have a significant relationship to the intestinal tract. When balance is restored, the symptoms are often resolved. Any improvement in the health of our intestinal tract increases the effectiveness of our immune systems.

The question currently being investigated by researchers is: Can we analyze the stool to create a map of all the different types and amounts of bacteria in the gut and use it to predict illness? We’re hoping it can be done.”

1 Michael D. Gershon, MD, The Second Brain (New York, HarperCollins, 1998).

2 Lipski, Digestive Wellness.

3 Hadhazy, “Think Twice.”

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Lipski, Digestive Wellness.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

Reprinted from Total Recovery: A Revolutionary New Approach to Breaking the Cycle of Pain and Depression by Gary Kaplan, D.O., with permission from Rodale Books. Copyright (c) 2014 by Gary Kaplan, D.O.

To read Part 2 of this series, “Hidden Immune System,” click here.